The big news of French football was the transfer of Michel Platini in the summer of 1979. That he was destined to play for a big club was obvious – Platini was already one of the biggest European stars and playing for Nancy was out of the question. The queastion was rather for whom he will play and it turned out, perhaps logically, he went to Saint Etienne. If France had anything similar to the European grands, it was St. Etienne in the 1970s. Dominant, successful, and wealthy enough to buy players at will. The great team of the mid-70s also aged and major reshaping was in the works as well, so it was seemingly the prime destination for Platini. Along with him, St. Etienne aquaired the services of another big star – Johhny Rep, who spent the last two years with Bastia. The point was made: St. Etienne really acted as a big club: when in need, getting the best, with the clear intention to continue its dominance. With this two transfers St. Etienne appeared too strong for the French league – on paper. The championship developed differently, or, rather, in traditional terms of French football. In short, St. Etienne did not win despite appearance. There was more than that, of course, but it concerned the end of the table. Two clubs reached pretty much the bottom of a decline started a few years back – Marseille and Lyon. Again, pretty much in accord with tradition: French football did not have mighty clubs, everybody experienced ups and downs and downs often meant relegation.

Brest finished last in the championship – a team well below any other.

Standing from left: RICO, ROCH, KEDIE, CORRE, GUENNAL, DE MARTIGNY, BOUTIER, JUSTIER, BERNARD.

Standing from left: RICO, ROCH, KEDIE, CORRE, GUENNAL, DE MARTIGNY, BOUTIER, JUSTIER, BERNARD.

Crouching: VABEC, GOAVEC, KERUZORE, MARTET, LETEMAHULU, LENOIR, HONORINE.

Kind of expected – apart from Vabec and Keruzore, nobody really classy. A small club, Brest was hardly able to compete with wealthier clubs, but even so the season was pathetic. They were the only team without away win and earned only 15 points from 4 wins and 7 ties.

If Brest was expected outsider, their immediate neighbours were not. Olympique Marseille – who would think. With 24 points, much stronger than poor Brest – but 24 points also meant they were 5 points behind the 18th placed.

Looking at the squad, it is unbelievable – Tresor, Six, Berdoll, Linderoth (Sweden) going to second division? Marseille started the 1970s as the top French club, but gradually went down – perhas by 1975 the signs of crisis were visible. The club rather desperately tried player after player, all big names, and nothing worked. Instead of going up, Marseille slowly sunk and finally was relegated. Perhaps the policy was wrong – Marseille had more money than most French clubs and therefore no trouble to get stars. The stars somewhat underperformed, or did not mix well with the other players, and were gone as quickly as they came. As for relegation – Marseille played second division in 1965-66 for the last. Welcome back…

Looking at the squad, it is unbelievable – Tresor, Six, Berdoll, Linderoth (Sweden) going to second division? Marseille started the 1970s as the top French club, but gradually went down – perhas by 1975 the signs of crisis were visible. The club rather desperately tried player after player, all big names, and nothing worked. Instead of going up, Marseille slowly sunk and finally was relegated. Perhaps the policy was wrong – Marseille had more money than most French clubs and therefore no trouble to get stars. The stars somewhat underperformed, or did not mix well with the other players, and were gone as quickly as they came. As for relegation – Marseille played second division in 1965-66 for the last. Welcome back…

Marseille was not theonly club in decline – Olympique Lyon was in the same situation. They finished 18th, with 29 points, so not in real danger, but just above the relegation zone.

Lyon mirrored Marseille – strong in the first half of the 1970s, they gradually faded away. Like Marseille, they were unable to replace outgoing players – the newcomers were somewhat of lesser class. Point in case: the current Yugoslavian imports, Aleksic and Zivaljevic, were not stars at all. Chiesa was getting too old. Tigana was not yet the famous player. Pretty much the same make like Marseille – and clearly not working.

Lyon mirrored Marseille – strong in the first half of the 1970s, they gradually faded away. Like Marseille, they were unable to replace outgoing players – the newcomers were somewhat of lesser class. Point in case: the current Yugoslavian imports, Aleksic and Zivaljevic, were not stars at all. Chiesa was getting too old. Tigana was not yet the famous player. Pretty much the same make like Marseille – and clearly not working.

The other declining clubs were Bastia – 16th this year, and Nice – 15th.

Standing from left: PAPI, MARCIALIS, BURCKARDT, KRIMAU, DE ZERBI.

Standing from left: PAPI, MARCIALIS, BURCKARDT, KRIMAU, DE ZERBI.

First row : MARCHIONI, HIARD, ORLANDUCCI, RAJKOVIC, CAZES, VERSTRAETE.

Nothing strange here – Bastia were normally found in the lower half of the table and their sudden climb to the top was unsustainable, for to stay there, the club needed stronger recruits. Buying good players was not financially possible. Keeping Johhny Rep was not possible either – and with him gone, Bastia immediately went down. Back to normal, so to say.

Nice, like Lyon and Marseille, was in decline, although their started earlier.

Having only a few strong players – Bjekovic, Bousdira, and perhaps Ferry – was no longer news. Nice was just keeping afloat and the queastion was for how long. There were no signs of improvement.

Having only a few strong players – Bjekovic, Bousdira, and perhaps Ferry – was no longer news. Nice was just keeping afloat and the queastion was for how long. There were no signs of improvement.

Those, who eather maintained relatively strong position or were slightly improving, were familiar names. Good season for Valenciennes – 8th place, but that only because they had worse goal-difference than Paris SG and Bordeaux.

To be in the top half of the table pretty much equals success for Valenciennes. They never had a truly strong team and this vintage was hardly more promising than earlier ones. It was even curiously strong year for a team whose most famous players were already veterans long beyond their peak – the former Polish national team defender Wrazy and the much-travelled Hungarian exile Ladinsky.

To be in the top half of the table pretty much equals success for Valenciennes. They never had a truly strong team and this vintage was hardly more promising than earlier ones. It was even curiously strong year for a team whose most famous players were already veterans long beyond their peak – the former Polish national team defender Wrazy and the much-travelled Hungarian exile Ladinsky.

Paris St. Germaine finished 7th, which was typical. Compared to Valenciennes, Paris SG was vastly superior – they had money and therefore stars. But Paris SG had stars for years and nothing good came out of it so far – the constant underachieavers of the league. 40 points – the same modest Valenciennes earned.

What was wrong with Paris SG? Perhaps their approach… finishing lower than hoped, they discarded expensive players, bought new expensive players, underperformed, discarded, bought, the vicious cycle . One Brazilian – Abel, one Portuguese – Alves, three French stars – Bathenay, Baratelli, Huck. What was common between them? They were all getting old… just like players Paris SG had before them. Perhaps Dahleb was the true star of the team, for he survived many purges, but… the star players were the newcomers. At the end, the former Paris SG player Toko, now with Valenciennes, finished equal to the expensive bunch. Somehow, Paris SG did not learn that a group of famous names is not yet a winning team.

What was wrong with Paris SG? Perhaps their approach… finishing lower than hoped, they discarded expensive players, bought new expensive players, underperformed, discarded, bought, the vicious cycle . One Brazilian – Abel, one Portuguese – Alves, three French stars – Bathenay, Baratelli, Huck. What was common between them? They were all getting old… just like players Paris SG had before them. Perhaps Dahleb was the true star of the team, for he survived many purges, but… the star players were the newcomers. At the end, the former Paris SG player Toko, now with Valenciennes, finished equal to the expensive bunch. Somehow, Paris SG did not learn that a group of famous names is not yet a winning team.

Also with 40 points, but with better goal-difference than Paris SG and Valenciennes, Bordeaux finished 6th. They were the only rising club – not ready to concur the league yet, but gradually going up.

On the surface, Bordeaux looked similar to Paris SG – a whole bunch fairly well known players, brought from other clubs. Some getting old, some already failing to become big stars. Lacombe, Gemmrich, Rohr, van Straelen. But here were also ambitious players, gradually becoming first rate – Giresse, of course, but also Domergue, Sahnoun, Soler, Lacuasta. Bordeaus was still shaping, but chemistry was good and the club was slowly going up. The most promising team at the moment.

On the surface, Bordeaux looked similar to Paris SG – a whole bunch fairly well known players, brought from other clubs. Some getting old, some already failing to become big stars. Lacombe, Gemmrich, Rohr, van Straelen. But here were also ambitious players, gradually becoming first rate – Giresse, of course, but also Domergue, Sahnoun, Soler, Lacuasta. Bordeaus was still shaping, but chemistry was good and the club was slowly going up. The most promising team at the moment.

The next two teams enjoyed strong years, but were not becoming big powers – they rather maintained positions. Strasbourg finished 5th.

Strasbourg, the champions of 1978-79, did what champions do – tried to enforce their team. The new big name was he top scorer Carlos Bianchi, formerly of Paris SG. Not a bad team, but the problem was age – Strasbourg was largely made of aging stars, who made their names elsewhere and were going downhill. The best such a team would do was exactly maintaining position among the best. Thus, a good season, but not in the title race – with 43 points, Strasbourg finished 7 points behind Monaco.

Strasbourg, the champions of 1978-79, did what champions do – tried to enforce their team. The new big name was he top scorer Carlos Bianchi, formerly of Paris SG. Not a bad team, but the problem was age – Strasbourg was largely made of aging stars, who made their names elsewhere and were going downhill. The best such a team would do was exactly maintaining position among the best. Thus, a good season, but not in the title race – with 43 points, Strasbourg finished 7 points behind Monaco.

Which was similar to Strasbourg.

4th place was fine, but also outside of the real competition. 4 points behind the bronze medalist.

4th place was fine, but also outside of the real competition. 4 points behind the bronze medalist.

St. Etienne took the bronze – may be a bit disappointed. 54 points, good attack, leaky defense…

St. Etienne came close to the big European clubs – unusual for France and showing ambition. But there was something missing – perhaps, the attempt to keep strong squad since 1970 blinded a bit Robert Herbin: inevitably, the squad aged and although strong, the peak was reached in the middle of the 1970s. The big transfers in the summer of 1979 confirmed ambitions, but also signaled a major change of approach: Platini and Rep, perhaps the start of building a new team. Not players,who would fit in, but players to lead and conduct the play. New leaders often need time so the others to get used to the new scheme. To a point, St. Etienne finished 3rd because this was reshaping year. But they did not win a title since 1976 and their last cup came in 1977 – perhaps the team needed more new players, a whole new team, if it was to begin winning again. Indicative of that was that they, with Platini and Rep, finished behind Sochaux.

St. Etienne came close to the big European clubs – unusual for France and showing ambition. But there was something missing – perhaps, the attempt to keep strong squad since 1970 blinded a bit Robert Herbin: inevitably, the squad aged and although strong, the peak was reached in the middle of the 1970s. The big transfers in the summer of 1979 confirmed ambitions, but also signaled a major change of approach: Platini and Rep, perhaps the start of building a new team. Not players,who would fit in, but players to lead and conduct the play. New leaders often need time so the others to get used to the new scheme. To a point, St. Etienne finished 3rd because this was reshaping year. But they did not win a title since 1976 and their last cup came in 1977 – perhaps the team needed more new players, a whole new team, if it was to begin winning again. Indicative of that was that they, with Platini and Rep, finished behind Sochaux.

Second row from left: Jean-Luc Ruty, Joël Bats, Abdel Djaadaoui, Moussa Bezaz, Bernard Genghini, Zvonko Ivezic

Second row from left: Jean-Luc Ruty, Joël Bats, Abdel Djaadaoui, Moussa Bezaz, Bernard Genghini, Zvonko Ivezic

Couching: Patrick Parizon, Eric Benoît, Yannick Stopyra, Patrick Révelli, Jean-Pierre Posca.

It was only thanks to better goal-difference Sochaux clinched silver, but for the usually insignificant club the season was fantastic. It was a good team, true, but nothing similar to St. Etienne – Stopyra and Bats were still promising youngsters. Stardom came a few years later. Ivezic was solid import, but ranking bellow other Yugoslavians. Genghini was fairly unknown yet too. As for Parizon and Petrick Revelli – they were let go from St. Etienne some time ago. Aging and no longer needed. The rejects finished ahead of their former club, however. All fine, but this was not a squad to take France by storm, let alone staying on top for long – one-time wonder, rather. Good, but not good enough to really run for the title.

Which went to an usual suspect – FC Nantes. Given the circumstances – some teams shaky, other not so strong, some other – not fine-tuned yet, and yet others in decline, Nantes was in shape, not ifs and buts. At the end, they finished 3 points ahead of Sochaux and St. Etienne.

Nantes was practically the only rival of St. Etienne during the 1970s, so they run similar risks: a squad established for years, slowly getting old, familiar, and may be no longer hungry. But Nantes was beginning the 80s strong and able, with little adjustments, to keep its leading position. Michel, Bertrand-Demanes, and Pecout were nearing retirement and gradually losing their edge, but Amisse, Rio, Tusseau, and particualry Bosis were in their prime – and in the national team. The foreign additions blended well – the Argentinian brothers Enzo and Victor Trossero. A squad in good shape by all means.

Nantes was practically the only rival of St. Etienne during the 1970s, so they run similar risks: a squad established for years, slowly getting old, familiar, and may be no longer hungry. But Nantes was beginning the 80s strong and able, with little adjustments, to keep its leading position. Michel, Bertrand-Demanes, and Pecout were nearing retirement and gradually losing their edge, but Amisse, Rio, Tusseau, and particualry Bosis were in their prime – and in the national team. The foreign additions blended well – the Argentinian brothers Enzo and Victor Trossero. A squad in good shape by all means.

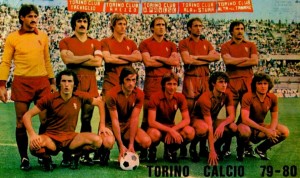

Standing from left: Terraneo, Claudio Sala, Volpati, Graziani, Pileggi, Vullo.

Standing from left: Terraneo, Claudio Sala, Volpati, Graziani, Pileggi, Vullo. Standing from left: Romeo Benetti, Turone, Ancelotti, Pruzzo, Di Bartolomei, Santarini.

Standing from left: Romeo Benetti, Turone, Ancelotti, Pruzzo, Di Bartolomei, Santarini.